Review by Mick Stephen

Background…

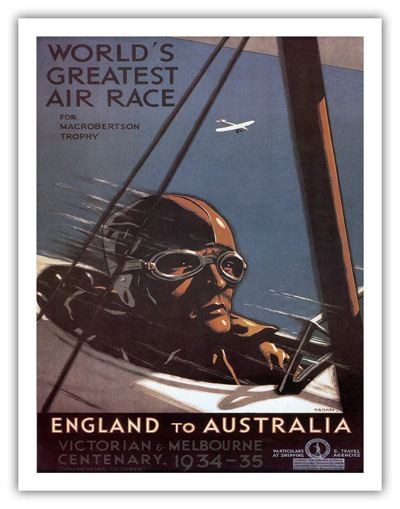

The MacRobertson Trophy Air Race (also known as the London to Melbourne Air Race) took place October, 1934 as part of the Melbourne Centenary celebrations. The idea of the race was devised by the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, and a prize fund of $75,000 (Australia used £ at that time) was put up by Sir Macpherson Robertson, a wealthy Australian confectionery manufacturer, on the conditions that the race be named after his MacRobertson confectionery company, and that it be organised to be as safe as possible.

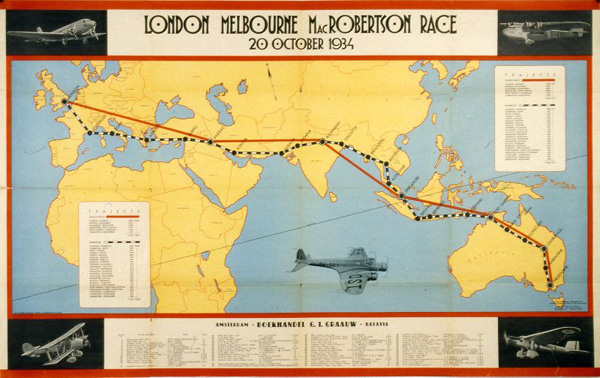

The race was organised by the Royal Aero Club, and would run from RAF Mildenhall in East Anglia to Flemington Racecourse, Melbourne, approximately 11,300 miles (18,200 km).

The basic rules were:

No limit to the size of aircraft or power, no limit to crew size, no pilot to join aircraft after it left England, aircraft must carry three days’ rations per crew member, floats, smoke signals and efficient instruments.

There were five compulsory stops at Baghdad, Allahabad, Singapore, Darwin and Charleville, Queensland; otherwise the competitors could choose their own routes. A further 22 optional stops were provided with stocks of fuel and oil by Shell and Stanavo.

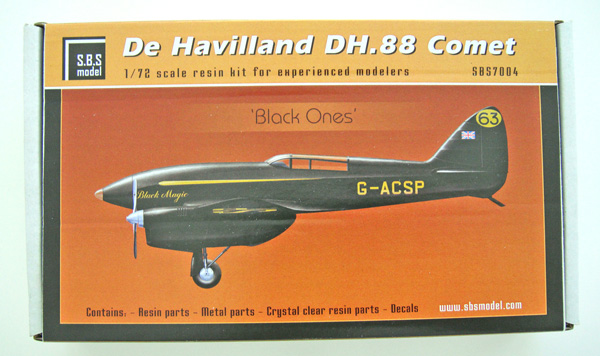

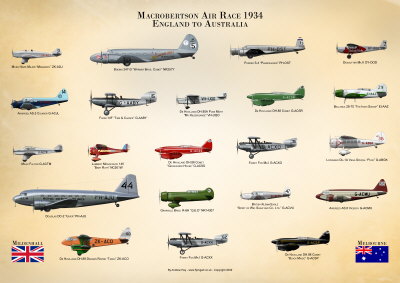

The competitors were of all shapes and sizes but we are focusing on only one type here, the purpose built De Havilland DH88 Comet Racer.

The forerunner of the Mosquito…

In January 1934 the De Havilland company offered to design a 200-mile-per-hour (320 km/h) aircraft to compete in the race and produce a limited number if three were ordered by February 1934. The sale price was to be £5,000 each (approximately £320,000 in 2016, when adjusted for inflation). This would by no means cover the aircraft’s development costs.

Three orders were received, and de Havilland set to work. The airframe consisted of a wooden skeleton clad with spruce plywood, with a final fabric covering on the wings. A long streamlined nose held the main fuel tanks, with the low-set and fully glazed central two-seat cockpit faired into an unbroken line to the tail. The wings were of a thin cantilever monoplane design for high-speed flight, and as such would require stressed-skin construction to achieve sufficient strength. While other designers were turning to metal to provide this extra strength, de Havilland took the unusual approach of increasing the strength of all-wood construction. De Havilland achieved the skin profile using many thin, shaped pieces set side by side, and then overlaid in the manner of plywood. This was made possible only by the recent development of high-strength synthetic bonding resins and its success took many in the industry by surprise.

This method of construction and the twin engine design is where De Havilland cut its teeth and went on to design and produce the infamous ‘wooden wonder’, the DH Mosquito.

The engines were uprated versions of the standard Gipsy Six, tuned for optimum performance with a higher compression ratio. The DH.88 could maintain altitude up to 4,000 feet (1,200 m) on one engine. The propellers were two-position variable pitch, made by French manufacturer Ratier, manually set to fine before takeoff using a bicycle pump and changed automatically to coarse by a pressure sensor. A drawback to the Ratier system was that the propellers could not be reset to fine pitch except on the ground. The main undercarriage retracted upwards and backwards into the engine nacelles, while the tailskid did not retract.

Landing flaps were placed slightly forward of the inboard wing trailing edge and continued in to the aircraft centre line. The forward fuselage was occupied by two large fuel tanks, with a third small tank located behind the cockpit.

With de Havilland managing to meet the challenging production schedule, delivery of the DH.88 to the three teams competing in the race began only six weeks before the start date. (source Wikipedia)

The three Comet’s were easily identifiable by their color:

Red: G-ACSS Grosvenor House

Black: G-ACSP Black Magic

Green: G-ACSR Un-named

“Black Magic” was owned and flown by Jim & Amy Mollison, but you may recognise Amy better from her maiden name “Amy Johnson”.

Only two further examples of the DH88 Comet were produced, F-ANPZ for the French Government as a mail carrier and G-ADEF named Boomerang which was lost during the Cape Town air race in 1935.